While there are many, many sources out there for in-depth learning about St. Elizabeths, we offer these bits of information as a supplement to the content contained on our website.

When did the Civil War military hospital open?

What’s up with using the different names? Isn’t it all St. Elizabeths Hospital?

How many soldiers were admitted to St. Elizabeths during the Civil War?

Why was the site selected for the Civil War military hospitals?

Why no apostrophe in the name of St. Elizabeths?

Who is buried in the Civil War Cemetery?

Where can I find records on my ancestor who was a patient?

Who was eligibile to go to the Government Hospital for the Insane?

When did burials begin in the Civil War Cemetery?

When did the Civil War military hospital close?

Do you have a photo of my ancestors gravestone?

Who was the first patient at the Government Hospital for the Insane?

I know my ancestor was at St. Elizabeths. Why can’t I find them in your search?

Why is the Civil War military hospital called St. Elizabeths?

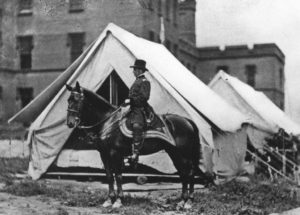

Did President Lincoln visit the troops at St. Elizabeths?

Who was the first female patient at the Government Hospital for the Insane?

When did they stop using the Civil War Cemetery?

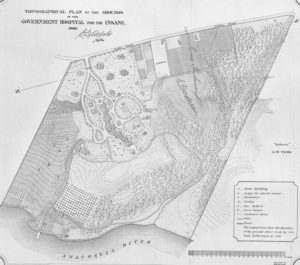

Wasn’t the Government Hospital for the Insane also a farm?

Were any notable Civil War soldiers admitted to St. Elizabeths?

When did burials begin in the John Howard Cemetery?

Didn’t the patients help to build St. Elizabeths using local materials?

What did the Government do to take care of disabled soldiers?

Who is buried in the John Howard Cemetery?

When did they stop using the John Howard Cemetery?

Can Veterans still seek care at St. Elizabeths today?

Is anything being done to recognize those buried in the unmarked graves at St. Elizabeths?

What does the future hold for St. Elizabeths?

Disclaimer

The information shared on this webiste about those buried in the cemeteries was gathered using publicly available resources. We are not associated with St Elizabeths Hospital in any way and encourage those researching their ancestors to contact them directly for specific information.